Behind the Bombay Buildings: A Study of Life in the Slums in Literary and Visual Media

Suman Bhagchandani, M.Phil. (English), University of Delhi

Bombay was central, had been so from the moment of its creation: the bastard child of a Portuguese-English wedding, and yet the most Indian of Indian cities. In Bombay all Indias met and merged. In Bombay, too, all-India met what-was-not-India, what came across the black water to flow into our veins…It was an ocean of stories; we all were its narrators, and everybody talked at once. (The Moor’s Last Sigh 350)

Rushdie’s novel, Midnight’s Children (1981) and The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995) has a single narrator-protagonist who takes the responsibility on his shoulders to narrate not only the history of Bombay, as a city, but the city as a microcosm of the nation. In each of the novels, the protagonist begins to write the family’s history, as the last male-heir, which is integrated into the larger history. The novels employ the method of bildungsroman by which the narrative figure explores the lives of the marginalised through a series of interactive incidents. Narrative depth is not the main focus of the novels which uses the channel of magic realism to highlight the subaltern discourses. The novels are structured with shifting terrains of focus (both geographically and theoretically) to bring the marginalised to the centre. In my paper I will refer to incidents of crime which are used as a trope for unsettling its institutional definition. Sudhir Patwardhan’s paintings and Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay! (1988) will be referred by me, in the second section of the paper, which focuses on slum representations of Bombay through visual media. The paper will thereby establish the argument that the centre and the marginalised are autonomous bodies, in a postmodern world, which also deconstructs the idea of the centre and the periphery.

Saleem Sinai, the narrator-protagonist of Midnight’s Children, born at the stroke of the midnight of 15th August, 1947, is given the power of ‘telepathy’ (200). Saleem’s ability to connect to millions of people across the country gave space to multiple voices inside his head, like an ‘All-India Radio’ (198), which he can modulate to serve his purpose (Note I). This talent which allows him to enter the people’s mind, or as he later discovers, to communicate with 420 other children who survived the midnight’s hour, also empowers him to voice the concerns of the people across the nation. However, if we consider the protagonist as not only the narrator of the history of the city of Bombay, but as the metaphor for the city itself, then we can consider these voices across the nation, of those people who migrated to Bombay across the ages. This migration did not come without the idea of ‘self-aggrandizement’ even as it did feel the need to control ‘the flooding multitudes’ for ‘their massed identities would have annihilated mine…’ (207) The xenophobia experienced by Saleem is reflective of the fear that Bombay had, as it was becoming the industrial capital of the nation. The city which was undergoing a transition, was also leading towards its self-effacement by giving space to multiple cultures and communities to thrive. But the rival that the city had to fear from was the increasing poverty. Shiva, the slumlord, Saleem’s midnight twin, is an embodiment of the economically marginalised community of Bombay. Born at the stroke of midnight, like Saleem, Shiva has strong knees—a physical ability which allows him to exercise power over others. The difference in opinion of Saleem and Shiva voices the failure of Jawaharlal Nehru’s second five year plan of economic development—a neocolonialist project of homogenising the two ends so as to create a nation cleansed of its poverty. While Saleem represents idealism and love for humanity, Shiva’s take on reality is materialistic. Shiva deflates the idea of secular socialism that Nehru promoted, to explain social Darwinism as the only truth that prevails in a capitalist society. Shiva’s birth at the same time as Saleem’s furthers the inevitable presence of poverty in a society—a constant reminder of the failure of Nehru’s ideals. Suketu Mehta in Maximum City, explains this in the context of post-Marxist structure of the city, which cannot escape social differences by ‘making the rich poorer’ to ‘make the poor richer’ (82) the manner in which Mary Pereira hopes to fulfil Joseph D’Costa’s dream of social equality in Midnight’s Children.

While Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children historicizes the tussle for space between the city and the slums of Bombay (and Delhi), The Moor’s Last Sigh looks at post-industrialization Bombay which invites slums to survive for its own existence. The latter novel places the protagonist, Moor Zogoiby, once again at the centre of the city of Bombay, which is fathered by two major powers, both of whom depend on the existence of the marginalised for their own survival. Abraham Zogoiby, with the help of his friend Kolatkar, the head of the Bombay Municipal Corporation team, declares the last group of migrants as illegal residents. Zogoiby then hires the same group of migrants to build high-rise buildings, on the land possessed by him, as cheap labour. ‘But naturally we accepted no responsibility in case of ill-health or injury…After all, these persons were not just invisible, but actually, according to official pronouncements, simply not at all there.’ (187) Mehta explores this historical change, when the Government in 1979, removed the fundamental right to property from the Constitution of India. According to the new law, large parts of the land in Bombay, after the lease expires, are liable to be transferred to the state. It creates doubt in the mind of the owners who are perpetually under the fear of being homeless. As a result of this, the new constructions do not take place. This has led to increase in slum dwellers which become twice the number every decade (126).

The other power which depends on the presence of the marginalised is represented by the head of Mumbai Axis, Raman Fielding. The representative of the Hindutva politics in Mumbai, Fielding is a fictional construct of the Shiva Sena leader, Bal Thackeray. Fielding, like Thackeray, believes in the purity of the city and creates a drive towards cleansing the city of its migrants and slums dwellers. Unlike Shiva who participates in the government’s drive to demolish the slums (Note II), Fielding uses the marginalised to serve his political purposes. By reclaiming the land from the migrants (through regional and linguistic hierarchy), and renaming it as Mumbai, after the Goddess of the fisherman folk, Mumbadevi, Raman Fielding brings the marginalised to the centre (both economically (Note III) and politically), while seeking their votes for his victory in politics.

Even as corruption becomes the tools by which the privileged dominate the subalterns (Note IV), the reversal of these power politics is also apparent in the two novels. Ranajit Guha describes the subaltern politics as having violent tendencies as it aims to resist the domination perpetuated by the elite (qtd. in Chaturvedi 10). If we view the two novels in this context, we can hear the voices of the marginalised that erupt in the process of the narration. Events like Musa’s stealing of the silver spittoon or Mary Pereira’s exchange of Sinai’s child with Winkie’s in Midnight’s Children become events in which the power politics is redefined. A similar event can be drawn from the second novel, where the protagonist is subjected to witnessing perpetual thieving in his house. Jaya, the maid silences Moor in order to continue stealing items from the Zogoiby household, which enables her to doubly subjugate him. When Moor tries to reverse the situation by confessing Jaya’s crimes to Lambajan, he is revenged upon by the maid and alienated by Lambajan.

Picture Singh the snake-charmer also practices alternate power politics in the ghettos of Delhi. He silences the congressman who advocates about equality amongst people across the nation, even as he recoils with the smell of dung. The snake-charmer performs a notorious trick with a cobra to prove, “the truth of the business: some persons are better, others are less. But it may be nice for you to think otherwise.” (477) In the later parts of the novel, Picture Singh opines about the lack of practicality in talking about Marx and Lenin to the uneducated, thus proposes to look into the ‘real’ problems prevalent in the ghettos rather than recite elite ideologies. He echoes the concerns of critics like Dipesh Chakrabarty who blames the Marxist ideologies in Third World countries to continue “the persistence of colonialist knowledge” (qtd. in Chaturvedi 18) Chakrabarty contests in his argument to replace Europe from the centre of the discourse with the nation’s history. Thereby, establishing a history that not only looks at class based subjugation but also cultural, religious, caste, and regional discourses.

Women who are doubly subjugated, through patriarchy and imperialism circumscribes them to specific roles in the society; caught between tradition and modernity, they are not allowed to exercise the existing discourses (Spivak 307). Parvati, the witch, and Padma (the narratee) however, invalidate these arguments by manipulating the power relations. Parvati, performs magic tricks to save Saleem from the government officials, but also obliges him to stay with her, and later take the responsibility of her child with Shiva. Breaking herself away from the traditional expectations, Parvati emerges as the modern woman who challenges the social norms of patriarchy. In a similar light, Padma’s what happened-nextism is a constant intervention into the authorial narrative that Saleem attempts to make. However, her approval of Saleem’s narrative overpowers him, and her absence paralyses him from further narration.

Padma’s play with Saleem’s ‘unmanliness’ post-sterilization programme (39) puts her in a dominant position who challenges the idea of patriarchy as well as offering him marriage to save herself from the shame of the world (530). The paradoxical nature of Parvati and Padma of tradition and modernity is also shared by Jaya in The Moor’s Last Sigh. Jaya’s frequent visits to the city in order to disapprove of its overcrowding streets is a mock at Aurora Zogoiby’s slum partying. This is furthered by Moor and the maid visiting her relatives at the chawls and not inhibiting herself from expressing disgust at the lack of facilities, unlike the generous Aurora who visits the ghettos and reconstructs them in a glorious manner for her paintings (Note V). Jaya’s resent at Moor, as she reminded him of his fortune to be born in an affluent family is an attack at the dominant class of the society.

The above instances from the two novels can thus be read as ‘assertion of the marginalised identity against the dominant discourse’ (Butler 57) which echoes the postmodern concern of the class fragmentation. The postmodern presence of the marginalised communities in the text, are an attempt to blur the boundaries drawn between the dominating and the dominated sections of the society. The play with the stereotypical representations of the society, instead of becoming the victim to it demands a separate identity deliberately disturbing the social hierarchy.

The second section of my paper looks at the representation of the Mumbai slums through visual media like paintings of Sudhir Patwardhan and Mira Nair’s bollywood production, Salaam Bombay! Both Patwardhan and Nair’s work recreate the slums of Bombay in order to disseminate the history of the city beyond its locale. As postmodern works of art, each of them historicize the rise in slums by stating migration as the main cause, while looking at other factors like industrialization and power politics. While Patwardhan participated in leftist politics prevalent in Bombay in the 80s, Nair does not claim any direct association with it. However, the common feature that places both these artists in the same canvas is the idea of the individual in a community, in the postmodern world. It is a celebration of the self which is constantly under the threat of homogenisation by the institutional ideologies of religion, class and caste.

Sudhir Patwardhan, a radiologist by profession, belongs to Thane, the suburban part of Mumbai. His art works on the subalterns of Mumbai are a manifestation of the leftist ideologies that he believed in. By bringing the periphery to the centre, Patwardhan questions the hierarchy maintained by the former artists’ works which are an attempt at constructing a national culture and identity. In an interview with Neville Tuli, the artist explains his relationship with his subjects as ‘I had a great need to identify with people outside my own class. This was, in a sense, growing out of one’s class, and commiting oneslf to an ideology, Marxism’ (354). Patwardhan’s subjects are usually slum residents engaged in daily chores, surrounded by the increasing number of industries centring towards them. As they fight for space in the city of Bombay, the streets become more crowded, and Patwardhan’s paintings become more intense. The paintings which began with slums as the focal point of concern have been replaced by high rise buildings which gradually make the slums vanish into non-existence. As we proceed further into his works, we observe the artist’s voyeuristic vision of the residents of the chawls, as the space between private and public life of Bombay decreases.

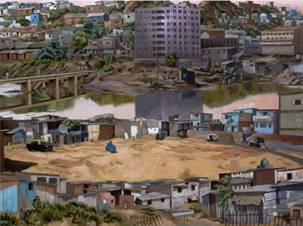

Illustration 1. The Clearance

The above painting by Patwardhan represents the outskirts of Mumbai, undisturbed by the city life. However, the low shacks are intimidated by the overwhelming industry which rises above them. The bridge which connects the two ends is symbolic of the rising development which offers vocation to the townsmen, even as it threatens to make these labourers landless (as the name suggests). The presence of transport vehicles in the remote sections of the town also indicates the blurring boundaries between the town and the city.

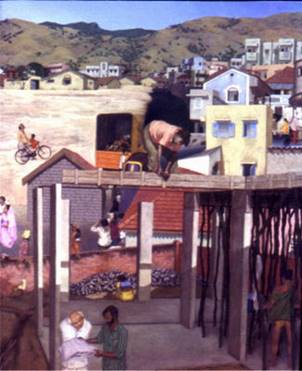

Illustration 2. Town

Illustration 3. Silent Town

The two paintings from the 1980s collection by Patwardhan progress upon the previous argument. The Town was an important turning point in his art, as he tells Tuli about his interest in miniatures that contribute to landscapes. The miniature details that concern Patwardhan in his early paintings are the life, social background and families (355). His interest in people is reflected in Town, which observes the chores of the labourers as they built the Town into a Silent Town. The near absence of the human subjects in Silent Town is indicative of further marginalisation of the poor as the town metamorphosis into a city.

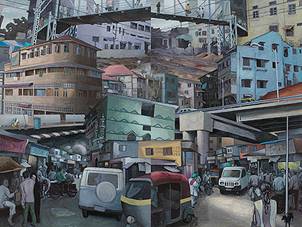

Illustration.4. Untitled

The above painting is from a collection of photographs across time and space, put in paint. This is a recent interest that Patwardhan had developed whereby he would capture the scene in a photograph to re-visit it through paint. This technique puts him among the group of artists like Bhupen Kakkar, Gulam Shaikh and Nalini Malini, who practice the art of “narrative painting” (Bhattacharya 66). A post-modernist style of painting which fragments a number of incidents and juxtaposes them across time-space axis, thus liberating it from its domain of performance. The city, in this painting, collapses towards the centre as the urban meets the slums and the roads run into the houses. The disintegration of multiple groups of people and institutions, into one canvas over-turns the flat style of painting, giving the picture a depth and narrative of its own in a palimsestic manner. This multi-layered narrative explodes with history of the topographical changes that were taking place in Bombay in the early twentieth-century, as it also explores the undisturbed continuity of life of the people.

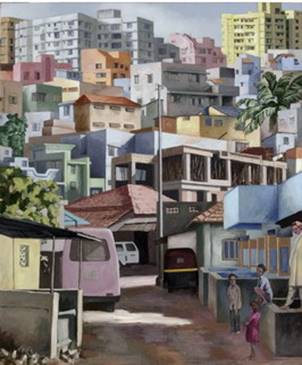

Illustration 5. Street Corner

Patwardhan painted Street Corner at the time when he was observing the development of town into the city. This painting gives a glimpse of the lives led by the people in the suburbs. The haphazard construction of the city (as in the previous painting) blurs the private and public boundaries, bringing the two ends together (Note VI). The painting shows a man leaning out of the balcony and into the street with a voyeuristic gaze, thus reversing the hierarchy of the inside and the outside.

The partial view of the private lives of the people, as Patwardhan travels across the city is furthered by Mira Nair in Salaam Bombay! The movie strips off the screen behind which the slums of Bombay were hidden, to celebrate its existence. Nair’s film is a tribute to the children of Bombay that belong to the streets and have to struggle with the whirlwind of crime, corruption, drug abuse and power politics for survival. The film narrates the life of a young boy, Chaipau who works for a travelling circus group but is deceived by his owner into alienation. Chaipau travels to the city of Bombay, the land of dreams, in the hope to earn Rs.500. Money becomes the focal point around which his life journeys, as it takes along with him other slum dwellers.

Chaipau, deprived of his last possession, is subjected to the life in a slum across the border of the railway tracks. The protagonist seeks illegal possession of the street as he willy-nilly becomes a part of the existing community. The shared economic deprivation of these children unites them across regions and religions which help them form an alternate community. Unlike most other children who lived on the scraps left by the people, or small scale robbery, Chaipau hopes to earn money through honest means. He serves tea in the chawl and it is through his visits to various households that we get a glimpse of the destitution that had settled in their lives.

A local network of drug dealership and prostitution is introduced as small-scale industries of crime in the slums. Lack of facilities and the need for survival results in an indulgence in these activities. While Chaipau expresses his disgust, as a newcomer to the society, others have already accepted these practices as routine activity. The society in the slums, as expressed through the film, does not follow regional or communal politics but exercises power through an alternative politics. The power practised by Baba, the drug-dealer or by the unnamed woman, the owner of the prostitution centre can be called, in Suketu Mehta’s term, ‘Powertoni: A power that does not originate in yourself; a power that you are holding on somebody else’s behalf. It is the only kind of power that a politician has: a power of attorney ceded to him by the voter’ (63). Both Baba and the prostitute dealer depend on vulnerable slum dwellers on whom ‘powertoni’ can be executed. Baba, employs possible drug addicts like Chillum, who are trapped in the cycle of consuming and selling the drug on which the former profits. Once Chillum’s life is ruined, Baba leaves him at the mercy of the streets and employs another vulnerable boy, who he again names Chillum.

By witnessing a series of crimes, Chaipau is acquainted with the scum in which they all reside and the inevitability of it. He, in his attempt to earn extra money, loses his employment and picks up odd jobs to collect money to return to his village, until he too is forced to participate in a petty crime. However, for Chaipau it is not crime which lands him in jail, but an honest job. Caught for loitering in the street, he becomes victim to institutional politics. The film shows at many levels, interaction between life in slum and the institutes of the government. The space for interaction of the marginalised and institutional power determines in whose favour the result would be. While the ghettos ostracize the foreign journalist who attempts to see the ‘real India’, Chaipau and his companion Manju, are subjected to the institutional laws in the city. The NGO which shelters Manju promises her a better life than the one she lived in the slums, even as they alienate her from her family.

Mehta concludes in an interview with a slum dweller,

We tend to think of a slum as an excrescence, a community of people living in perpetual misery. What we forget is that out of inhospitable surroundings, they form a community…Any urban development plan has to take into account the curious desire of slum dwellers to live closely together. A greater horror than open gutters and filthy toilets…is an empty room in the big city. (60)

Notes:

I) This is a skill that he possesses which enables him to silence Shiva, after he discovers the truth about his and Shiva’s identity. Silencing Shiva becomes important to him to be able to continue to exert power in a class-based society (even as a child) and not interfere with the process that Mary Periera had initiated.

II) Sanjay Gandhi’s beautification programme.

III) Here we can once again draw a parallel from Mehta’s case study of Sunil, a slum dweller who actively engages in practicing Hindutva politics in his area. Even though he continues to stay there, it is assured that he is economically secure.

IV) Reading subalternity through Guha’s study of class heterogeneity in the society.

V) Aurora Zogoiby’s slum partying is a reference to painters like Abanindranth Tagore and Amrita Sher-Gil who glorified the Indian villages in their paintings for a larger, nationalist project. Also, the fact that Zogoiby’s painting exhibitions are addressed only to the elite members of the society, as she prevents it from turning into a mass movement, puts her in a dominant position.

VI) An interesting documentary in this light has been made by Prahlad Kakkar called Bumbay: The Shit Capital of India. The documentary shows how lack of space in the city has forced people to perform a private activity like defecation, in public. It challenges the municipal authority whose function is to keep the city clean, but whose function is also to provide adequate space to reside. Questions of private and public domains become insignificant in this situation.

Bibliography

Rushdie, Salman. Midnight's Children. New York: Avon Books, 1981.

--. The Moor's Last Sigh. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995.

Mehta, Suketu. Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2004.

Chaturvedi, Vinayak. “A Critical Theory of Subalternity: Rethinking Class in Indian in Hitoriography.” Left History 1 (2007): 9-28.

Bhattacharya, Malini. “The Second Kasauli Seminar on Aesthetics.” Social Scientist 10.8 (1982): 64-71.

Kumar, R. Siva. “Modern Indian Art: A Brief Overview.” Art Journal 58.3 (1999): 14-21.

Patel, Gieve. “Contemporary Indian Painting.” Daedlus 118.4 (1989): 170-205.

Patwardhan, Sudhir. Illustration 2. Town. 1984.

––. Illustration 1. The Clearing. n.d.

––. Illustration 3. Silent Town. 2007.

––. Illustration 4. Sakshi Gallery Exhibition. Untitled. 2007-08.

––. Illustration 5. Street Corner. n.d.

Lipscomb, David. “Caught in a Strange Middle Ground: Contesting History in Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children.” A Journal of Transnational Studies 1.2 (1991): 163-89.

Katawal, Ubaraj. “In Midnight's Children, the Subalterns Speak!” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies , 5.1 (2013): 86-102.

Bhabha, Homi K. “DissemiNation: Time, Narratives and the Margins of the Modern Nation.” Bhabha, Homi K. Nation and Narration. New York: Routledge, 1990. 291-321.

Tharoor, Shashi. The Great Indian Novel. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1989.

Shah, Nila. Novel as History. New Delhi: Creative Books, 2003.

Thapar, Romila. “Decolonizing the Past.” Readings in Early Indian History. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2013. 3-21.

Salaam Bombay! By Sooni Taraporevala Mira Nair. Dir. Mira Nair. Perf. Hansa Vithal, Nana Patekar, et al. Shafiq Sayed. Prod. Gabriel Auer Mira Nair. 1988.

Bumbay: Shit Capital of India. Dir. Louis Banks, Javed Jaffery, et al. Prahlad Kakar. 2012.

Tuli, Neville. “Sudhir Patwardhan.” Flamed mosaic: Indian contemporary painting. Delhi: Grantha Corp, 1997. 354-357.